Missing, But Not Forgotten

Whatever happened to "lost boy" Etan Patz?

A New York Times headline -- “Conviction Reversed in Etan Patz Case That Put Focus on Missing Children” -- immediately caught my eye and brought me back to another era, a lost but not forgotten time.

I covered the story of Etan Partz’s disappearance when I was working at the Soho News, a weekly focused on the up-and-coming artist neighborhood in transition. As families moved into the recently landmarked cast iron buildings, the one-time desolate streets teemed with mommies and nannies pushing strollers, their older kids running alongside them. Given the overall sorry state of the city rife with crime, drugs and burned-out buildings, Soho was thriving as bars, boutiques and galleries offered the potential of a brighter future.

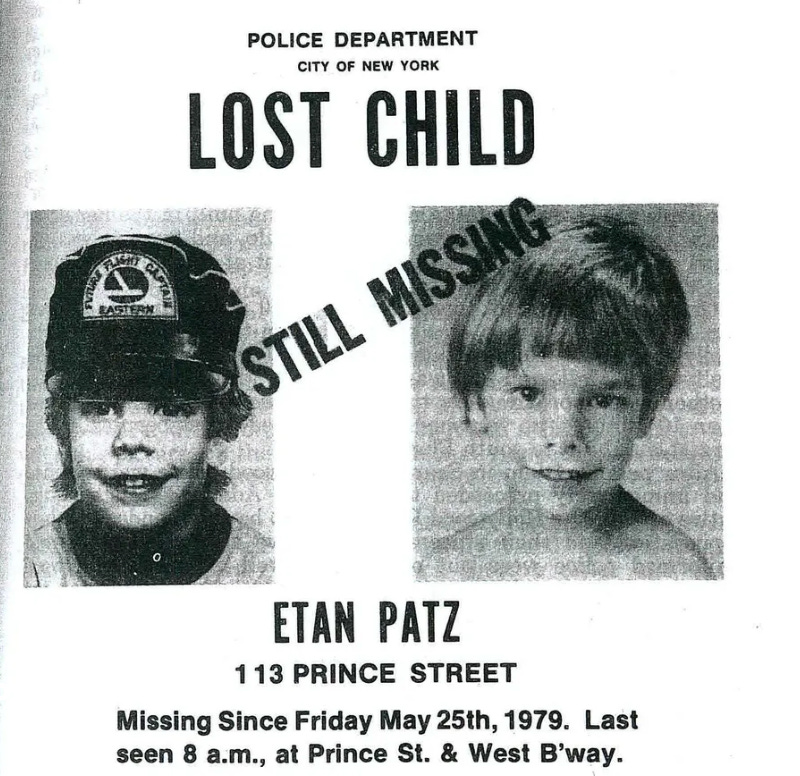

In May, 1979, a 6-year-old local boy named Etan Patz went missing, never seen again after leaving home to go to school on the city bus, the very first time he had been allowed to do so. The disappearance set off a community-wide search party and postering campaign that grew into a national news story. The posters were everywhere, a recurring nightmare that changed New York parenting guidelines forever. He was the first “lost boy” to have his picture on the side of a milk carton. After years of investigation with no progress, in 2012, Pedro Hernandez was convicted of the murder. Now a Federal Appeals Court has overturned his conviction based on a violation of his Miranda Rights.

I remember visiting the Patz family SoHo loft on Prince Street, climbing the long staircase, dreading a meeting with grieving parents who were also under suspicion because… well, they were his parents, and the police must begin somewhere. There were no clues and apparently no one had seen anything unexpected that day. Two cops logged phone calls coming into the house, the parents already too worn out to answer themselves. It was hard for all of us, for them to repeat what they had been telling a stream of investigators and reporters and for me to hear the sad story told through their tear-streaked faces. A boy matching Etan’s description was seen in a playground at LeRoy Street and Seventh avenue in the Village. The police want the boy’s father, Stanley, to go to the park with them. I tag along and we drive over in a police car.

I’ve never been in a police car. I’ve run from police, hid my weed from police, protested police brutality and generally associated them with all things Nixon. I assumed that cops were human too, but this was the first time I’d ever seen them genuinely concerned and empathetic. They’d been around long enough to smell tragedy in the air

.At the park, we spread out. I investigated its dark corners and shadows looking for anything that might provide a clue to his whereabouts. A blue shirt near a broken bat in the baseball field caught my eye. The detective asked me to show the shirt to his father, Stan, who held it up, trying to imagine it on Etan, though it was several sizes too large and unlike anything the boy had at home.

At Third Street and MacDougal, we spotted a young boy at a pizza stand who matched Etan’s description. We pulled over and the cops jumped out. “He doesn’t eat pizza,’” says Stan after they returned. “Pizza has cheese on it. Cheese is something adults eat.”

By 10 pm, we were back in the loft, a radio playing opera softly in the background. A cop talked on the phone and wrote in his log. Etan’s mom, Julie, made coffee and light conversation. “We have to think positively,” she smiled.

In 1983, President Ronald Reagan proclaimed May 25 as National Missing Children’s Day in honor of Etan’s memory.

Remember your story and of course the Patz case well, old friend.